Snoring

| Snoring | |

|---|---|

| |

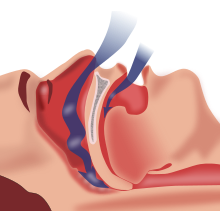

| The soft palate and the base of tongue obstruct the airway in a person sleeping on their back. Snoring is one of the major symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea, although it may occur without any sleep apnea or other medical conditions. | |

| Specialty | Otorhinolaryngology, sleep medicine |

Snoring is an abnormal breath sound caused by partially obstructed, turbulent airflow and vibration of tissues in the upper respiratory tract (e.g., uvula, soft palate, base of tongue) which occurs during sleep. It usually happens during inhalations (breathing in).

Primary snoring (also termed simple snoring, non-apneic snoring, or habitual snoring) is snoring without any associated sleep disorders and without any health effects. It is usually defined as apnea–hypopnea index score or respiratory disturbance index score less than 5 per hour (as diagnosed with polysomnography or home sleep apnea test) and lack of daytime sleepiness.

Snoring may also be a symptom of upper airway resistance syndrome or obstructive sleep apnea (apneic snoring). In obstructive sleep apnea, snoring occurs in combination with breath holding, gasping, or choking.

Classification

[edit]In the International Classification of Sleep Disorders third edition (ICSD-3), snoring is listed under "Isolated symptoms and normal variants" in the section "Sleep-related breathing disorders". The manual defines snoring as "a respiratory sound generated in the upper airway during sleep that typically occurs during inspiration but may also occur in expiration."[1]

Primary snoring (also termed simple snoring, non-apneic snoring, habitual snoring, or isolated snoring) is snoring without any other associated medical condition.[2][1] Primary snoring is not associated with episodes of sleep apnea (cessation of breathing), hypopnea, respiratory-effort related arousals, or hypoventilation.[1] There are no significant effects for the individual (such as daytime sleepiness or insomnia) or for a sleeping partner, although primary snoring may wake the individual or their sleeping partner.[2][1] However, the idea that primary snoring without sleep apnea has no effects on quality of life is increasing challenged.[3][4][5] For example, there is evidence that non apneic snoring, which is not associated with any sleep-related breathing disorder, causes excessive daytime sleepiness.[5]

Therefore, primary snoring cannot be diagnosed in the presence of sleep apnea.[1] Snoring is one of the main symptoms of obstructed sleep apnea, where it may be termed apneic snoring.[1] In obstructed sleep apnea, snoring occurs in combination with other features such as breath holding (breathing cessation), gasping, or choking.[1] There are also other features like daytime sleepiness, nonrestorative sleep, fatigue, or insomnia.[1]

Snoring has also been classified according to frequency as occasional snoring (occurring on three nights or less per week) and habitual snoring (occurring on most nights, synonymous with primary snoring).[6]

Snoring has been classified according to apnea–hypopnea index score and severity of associated sleep disorders. Therefore, snoring as a symptom exists as a spectrum of severity, with primary snoring being the least severe, snoring with upper airway resistance syndrome being of intermediate severity, and snoring associated with obstructive sleep apnea being the most medically significant.[2] Obstructive sleep apnea may be subdivided into mild, moderate, and severe types.[7]

- Asymptomatic, non-apneic snoring (primary snoring). No daytime sleepiness and apnea–hypopnea index less than 5 per hour.

- Non-apneic snoring with upper airway resistance syndrome. Daytime sleepiness and apnea–hypopnea index less than 5 per hour. Between 5 and 10 respiratory-effort-related arousals per hour. Oxygen saturation more than 90%.

- Apneic snoring (snoring associated with obstructive sleep apnea). Apnea–hypopnea index more than 5 per hour. Oxygen saturation less than 90%. Deviating pattern on electroencephalogram.

Primary snoring is occasionally defined as apnea-hypopnea less than 15 (or less than 10) with body mass index less than 32 kg/m2. It has been suggested that individuals with primary snoring may gradually progress towards obstructive sleep apnea[5] as causative factors such as aging and obesity change over time. However, there is limited evidence for this. 37% of children with primary snoring progressed to obstructive sleep apnea after 4 years.[5] On the other hand, in many cases snoring is resolved over time rather than getting worse.[2]

Snoring severity has also been classified according to average maximum volume:[3]

- Mild (40-50 decibels)

- Moderate (50–60 dB)

- Severe (>60 dB)

In snoring associated with obstructive sleep apnea, louder snoring is correlated with severity of sleep apnea.[3] On average, males snore more loudly than females, and people with higher body mass index snore louder than those with lower body mass index.[3]

Mechanism

[edit]

Snoring has been mathematically modelled wherein the upper airway is a tube which has an elastic or collapsible section. As the section of the upper airway narrows, resistance to the flow of air increases.[3] There is a cyclical obstruction and reopening of the airway at the partially or fully collapsed section as air flows past.[7] This obstruction and reopening occurs at approximately 50 times per second, which causes vibration and noise.[7] The airflow becomes unstable and turbulent.[3]

The structures that obstruct the airway and vibrate are various soft tissue structures at different levels along the upper respiratory tract or aerodigestive tract.[2] These are the uvula, soft palate, faucial pillars (palatoglossal arch, palatopharyngeal arch), palatine tonsils, adenoid tonsil, walls of the pharynx, epiglottis, or lower structures.[1][3][8] These structures may relax during sleep and move position, especially under the influence of gravity. This results in partial obstruction (narrowing) or complete obstruction of the airway. Partial obstruction of the airway is more associated with primary snoring, whereas complete obstruction is more a feature of obstructive sleep apnea.[9] The following structures were found to vibrate during snoring: soft palate in 100% of cases, pharynx (53.8%), lateral pharyngeal wall (42.3%), epiglottis (42.3%), and tongue base (26.9%).[7] In primary snoring there may be vibration of the soft palate alone, termed "palatal fluttering". In mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea, there may be vibration of the palate and lateral pharyngeal wall. In severe obstructive sleep apnea, there may be vibration of the tongue base and epiglottis in addition to the above structures.[7]

The snoring sound mainly occurs during inspiration (breathing in), but it may occur during expiration (breathing out).[2] Snorers have more negative pressure in their airway, increased inspiratory time, and limitation of respiratory flow.[3] On polysomnography, snoring is usually louder during stage N3 sleep or rapid eye movement sleep.[1] Snoring in obstructive sleep apnea usually occurs when airflow turbulence is maximum, which is during hyperpnea episodes at the end of apnea events (breathing cessation).[7]

Causes

[edit]Snoring is often considered according to the location (level) of structure that is causing the obstruction and vibration. However, the sites causing the snoring vary from one person to the next, and the same individual may have multiple different sites which are contributing to the problem.[10]

Nasal cavity

[edit]

The nasal cavity causes over 50% of the total airway resistance, particularly at the internal and external nasal valves.[7] The internal nasal valve is located approximately 1.5 cm from the nostril and constitutes the narrowest part of the upper airway.[11] The external nasal valve is the tissue immediately around the nostril. Nasal valve collapse refers to weakening or narrowing of the supporting cartilage at the nasal valves. As per the Hagen–Poiseuille equation, a minimal reduction in the diameter of a tube (in this case the nasal airway) results in an exponential change in airflow.[12] Nasal valve collapse is a cause of snoring.[10][12]

Nasal congestion (nasal obstruction) reduces sleep quality.[7] Common reasons for nasal obstruction are allergic rhinitis and nonallergic rhinitis.[7] Nasal septum deviation and inferior turbinate hypertrophy (enlargement) are present in almost all cases of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea.[7] Masses in the nasal cavity such as nasal polyps or tumors may also cause snoring.[9][10]

Adenotonsillar hypertrophy

[edit]Adenoid hypertrophy (enlargement of the adenoid tonsil) and tonsillar hypertrophy (enlargement of the palatine tonsils) is associated with snoring and obstructive sleep apnea,[13][1][4] especially in children since the tonsils are larger at younger ages. Adenotonsillar hypertrophy is the most common cause of snoring in children.[10]

Mouth

[edit]Dental problems may be conditions associated with snoring rather than direct causes. Examples include malocclusion, crowding of upper teeth, narrow palate,[4] and high-arched palate. Narrow palate and high arched palate create a predisposition to chronic nasal obstruction.[7]

Mouth breathing

[edit]Mouth breathing frequently accompanies snoring as one of main features of sleep-related breathing disorders (including primary snoring, upper airway resistance syndrome, and obstructive sleep apnea).[14] In one study, 18% of people with mouth breathing reported awareness of snoring.[14]

Retrognathia

[edit]Retrognathia (receded lower jaw) is more common in obstructive sleep apnea than in primary snoring.[7] Micrognathia (small jaw size) is also linked to snoring.[4]

Pharynx

[edit]The muscles of the pharynx relax during sleep, causing partial airway obstruction.[10]

Tongue

[edit]When sleeping on the back, gravity pulls the tongue backwards and may obstruct the airway.[15] An enlarged tongue, termed macroglossia, is a potential cause for snoring.[10] Obesity may result in increased tongue size.[3] The base of the tongue may be enlarged and cause snoring, e.g. because of a tumor.[10]

Larynx and laryngopharynx

[edit]Problems within the larynx ("voice box") and laryngopharynx may cause snoring, such as laryngeal stenosis or an omega-shaped epiglottis.[10]

Obstructive sleep apnea

[edit]Snoring is one of the cardinal symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea.[1] People who snore are five times more likely to have obstructive sleep apnea compared to those who don't snore.[7] Snoring is common in upper airways resistance syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea is almost always associated with snoring.[9]

Obesity

[edit]Being obese or overweight increases the amount of fat around the throat. It is not just body mass index that is important, but the circumference of the neck (e.g., collar size more than 42 cm)[10] and the size of the tongue.[3] Snoring is three times more common in obese individuals.[9] Obesity hypoventilation syndrome also involves snoring.[9]

Alcohol

[edit]Alcohol causes muscle relaxation via its depressant effect on the central nervous system. This muscle relaxation seems to be more pronounced for the tongue,[3] which may then be more prone to obstruct the airway.

Muscle relaxants

[edit]Medications that cause muscle relaxation such as sedatives and hypnotics may cause snoring or make it worse. One example is diphenhydramine.[3]

Diet

[edit]Magnesium is a micronutrient which may have a role in maintaining circadian rhythm and sleep quality.[16] There may be a connection between higher magnesium intake and sleep quality, which includes factors such as snoring, daytime sleepiness, and sleep duration. One study supported this connection. Another study showed that 332.5 mg/day magnesium did not have any effect on sleep symptoms such as snoring and sleepiness.[16]

Pregnancy

[edit]Sometimes snoring starts during pregnancy.[1][17]

Genetics

[edit]Some people have a genetic predisposition to snoring, a proportion of which may be mediated through other heritable lifestyle factors such as body mass index, smoking and alcohol consumption.[18] The DLEU1 gene (part of BCMS) has been linked to snoring.[19]

Possible consequences

[edit]Most people with primary snoring do not have any significant health problems as a result of the snoring.[20]

For sleeping partner

[edit]It is sometimes suggested that snoring is more of a problem for the sleeping partner than the person who snores.[3] Snoring of one partner may cause marital discord, and sometimes has lead to a divorce.[10] The term "snoring spouse syndrome" has been used to describe the health effects for sleeping partners of people with obstructive sleep apnea.[9][10] Snorers may be unaware of the their snoring.[3] It may be difficult for sleeping partners to adjust to the noise because snoring may be irregular, changing in volume and character.[3] This may wake them and prevent them from falling asleep again.[3] Sleeping partners may try to nudge the snorer. This may trigger the snorer to change position, or it may rouse them sufficiently to reduce the muscle relaxation in the upper airway, lessening the snoring.[3]

In one study, treatment of snoring in males (with continuous positive airway pressure) resulted in 13% better sleep efficiency and an average of 1 hour of extra sleep for their female sleeping partners.[3] 1 hour of lost sleep per day equates to a whole night of lost sleep each week. This may result in chronic sleep deprivation for sleeping partners of snorers.[3] It has also been reported that sleeping partners of snorers may gradually develop hearing loss, although there is little evidence for this. In one small study, sleeping partners had detectable hearing loss in the ear that was habitually facing the snorer.[3]

Parents of children who snore may also suffer reduced sleep quality.[4]

Cognitive and psychological

[edit]Snoring may cause sleep deprivation for snorers. Snoring, even when not associated with obstructive sleep apnea, has been linked to excessive daytime sleepiness.[5] Snoring may cause other problems such as irritability,[10] depression,[10] memory loss,[10] fatigue,[10] lack of focus and decreased libido.[10] It has also been suggested that it increases the risk of road traffic accidents.[10]

In children, snoring may affect growth.[4] It may also affect mood, attention, intelligence, and reduce academic performance at school.[1][4][9] Snoring may manifest as behavioral problems, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.[4][9]

Cardiovascular disease

[edit]Some studies report that there is a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease in snorers. This includes metabolic syndrome,[20] hypertension (high blood pressure), stroke, and ischemic heart disease.[1] There may be up to a 46% increased risk of stroke.[21] The reason for this association may be that snoring may increase the risk of atherosclerosis, which is a predisposing factor for stroke.[21] It is known that sleep apnea causes hypoxemia, oxidative stress, inflammation, insulin resistance, dysfunction of endothelium, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension.[21] However, not all studies report increased risk of cardiovascular disease in those who snore.[1][21] Snoring that starts during pregnancy may be linked with higher risk of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia.[1][17]

There is limited evidence that snoring may cause atherosclerosis of the carotid artery.[1] In research on animals, vibration energy from snoring may be transmitted to the carotid artery. This vibration causes damage to the endothelium. The binding ability of low density lipoprotein may also be increased by acoustic waves.[3] In other words, vibrations from snoring may damage blood vessels, cause formation of atherosclerotic plaque, and also increase the probability that the plaque ruptures.[21] Both non apneic snoring and snoring associated with obstructive sleep apnea have been correlated with carotid atherosclerosis, carotid artery stenosis, and other carotid disease in humans.[3] In one study, snorers had 50% higher chance of carotid stenosis and were more likely to have carotid disease on both the left and right sides.[3]

Headaches

[edit]Snoring is also linked to headaches and migraines, especially headache upon waking.[5] This may be related to cerebral hypoxia, hypercapnia, and temporary increased intra-cranial pressure.[5] Snoring is associated with respiratory event-related arousals, which may be connected with headache.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

[edit]Snoring and obstructive sleep apnea are associated with higher rates of gastroesophageal reflux disease, including acid reflux which occurs during sleep.[5] There is increased negative pressure in the thoracic cavity during apneic episodes. It was suggested that this negative pressure may overcome the lower esophageal sphincter and allow stomach contents to reflux into the esophagus. However, the lower esophageal sphincter was found to be stronger during obstructed breathing events. Another theory which explains the connection is that snoring and obstructive sleep apnea may promote transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations.[5] Enlarged tonsils are also seen in gastroesophageal reflux disease,[5] and this may contribute to airway restriction and snoring.

Sleep bruxism

[edit]There is conflicting evidence for and against a possible connection between snoring and sleep bruxism (teeth grinding during sleep). It may be that in snoring and obstructive sleep apnea, there are periods of activation of oropharyngeal muscles. These are necessary to restore patency of the collapsed / obstructed airway. This muscle activity may also trigger activity in the muscles of mastication and hence sleep bruxism.[5]

Dry mouth

[edit]There is limited and contradictory evidence for a connection between snoring and xerostomia (dry mouth).[5] Tissue biopsies of the uvula have been carried out on heavy snorers and people with severe obstructive sleep apnea. The biopsies showed abnormal minor salivary glands. There was increased volume of mucous salivary glands and reduced quantity and volume of serous salivary glands. This may cause reduced production of saliva. Snorers also tend to breath through their mouths during sleep, in order to get more air. This may have a drying effect in the mouth.[5]

Other

[edit]Nerve damage may occur in the soft palate as a result of chronic trauma from vibration. This is leads to morphological changes in the palate.[1]

Diagnosis

[edit]Primary snoring may only be diagnosed when obstructive sleep apnea has been ruled out.[3] This usually requires a sleep study.[3] A sleep study includes calculation of the apnea–hypopnea index, and measurement of many other parameters such as the total number of snoring events, flow limitations without snoring (indicates nasal obstruction), and flow limitation with snoring (indicates obstruction from palate and tongue base).[9] Home sleep apnea test is another option, allowing calculation of apnea-hypopnea index and respiratory disturbance index and differentiation between primary snoring and obstructive sleep apnea.[20]

Bronchoscopy may also be carried out.[4] Anterior rhinoscopy and nasal endoscopy may be done which may identify problems inside the nose such as deviated septum, hypertrophic inferior turbinate, or nasal polyps.[9]

Questioning of not just the snorer but also their sleeping partner may be useful in the diagnostic process.[3] An audio recording of the snoring may also be useful.[3]

Palatal snoring (caused by vibration of the soft palate) has an average peak frequency of 137 hertz. Snoring caused by the tongue base has 1243 Hz. Combined palatal and tongue snoring has 190 Hz. Snoring caused by epiglottis has 490 Hz.[3]

Treatment

[edit]Almost all treatments for snoring revolve around lessening the noise and improving air flow by reducing the blockage in the airway.

Lifestyle modification

[edit]Lifestyle changes are a first-line treatment to stop snoring.[22] Recommended lifestyle changes include stopping smoking, avoiding alcohol before bedtime,[23] and sleeping on the side.[10] Sleeping on the side reduces the tendency for the base of tongue to fall back and obstruct the airway (which occurs when sleeping on the back, since gravity pulls the tongue backwards in this position). Losing weight reduces the amount of fat that compresses the airway. Even a modest amount of weight loss, such as 4.5 kg (10 lbs) can improve snoring.[3]

Improving sleep hygiene may be beneficial. Examples include establishing fixed routines for bedtime and wake up time, including on weekends.[4] Relaxation before sleep may help people get to sleep more quickly. Applications for smartphones and smartwatches are available. They often record snoring during sleep, compare snoring severity over time, and give advice to users. Some apps trigger a sound or vibration when the person starts to snore.[3] Many over-the-counter snoring treatments, such as stop-snoring rings or wrist-worn electrical stimulation bands, have no scientific evidence to support their claims.

Nasal strips

[edit]Many types of nasal strips, nose clips, and internal dilators are available to temporarily prevent nasal valve collapse. They all are designed to stent and expand the internal nasal valve.[12]

Orthopedic pillows

[edit]Orthopedic pillows are designed to support the head and neck in a way that ensures the jaw stays open and slightly forward. This helps keep the airways unrestricted as possible and in turn leads to a small reduction in snoring.

Medications

[edit]Medications are usually not helpful in treating snoring symptoms, though they can help control some of the underlying causes such as nasal congestion and allergic reactions. Corticosteroid nasal sprays can reduce inflammation in nasal mucosa and reduce the size of the adenoid, thereby reducing symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea such as snoring.[4] Montelukast has also been used in the same application.[4]

Medications that aggravate snoring such as sedatives may be avoided before bedtime, or they may be substituted for weaker alternatives.[3]

Myofunctional therapy (oropharyngeal exercises)

[edit]Myofunctional therapy incorporates oropharyngeal (mouth and throat) and tongue exercises. The exercises are usually combinations of isotonic and isometric exercises involving different muscles of the soft palate, tongue, face, pharynx, jaw, and upper respiratory tract.[24] Pronouncing vowel sounds activates muscles in the soft palate and uvula.[25] Tongue exercises may involve movement of the tongue in different directions, sticking out the tongue, and pressing the tongue against hard and soft tissue surfaces in the mouth.[25] Facial exercises may involve pushing out the cheek with a finger while puckering, closing, or moving the lips.[25] Jaw exercises may involve chewing[24] and opening and closing the mouth.[25] Pharyngeal exercises may involve swallowing.[25] Other exercises include sucking through a narrow straw and blowing up balloons.[25] Myofunctional therapy is theorized to improve the tone and positioning of the muscles.[25] The exercises may promote a closed mouth breathing position where the tongue is in contact with the palate.[25] This may create negative pressure in the mouth, leading to a stabilization of patency of the pharynx and reduced muscular effort required to keep the airway open.[25]

There is conflicting evidence for the effectiveness of myofunctional therapy in snoring.[24] One systematic review found that myofunctional therapy reduces snoring in adults based on both subjective questionnaires and objective sleep studies.[25] Snoring intensity was reduced by 51%.[25] Time spent snoring was reduced by 31% as measured by polysomnography.[25] One study used objective measurement of snoring (audio recordings) and found that myofunctional therapy had little to no effect in reducing snoring frequency.[24] Another study reported that myofunctional therapy had a possible reduction in snoring frequency and intensity (measured subjectively) compared to sham therapy (placebo).[24] When myofunctional therapy combined with CPAP is compared to myofunctional therapy alone, there may be little to no difference.[24] Myofunctional therapy may be more useful in children who snore than in adults.[9]

Dental appliances

[edit]

Dental appliances are common treatments for snoring. They may be custom made, which requires an impression of the teeth and construction in a dental laboratory, or bought over the counter without involvement of a dental health professional. In general oral appliances are cheap and non invasive.[9] They can be combined with CPAP treatment.[9] Complications include discomfort, excessive salivation (drooling),[9] insomnia,[9] pain in the periodontal ligament of teeth if they are under excessive force, pain in the temporomandibular joint[9] and muscles of mastication (e.g. temporalis), and jaw dislocation.[9] Some devices prevent anterior oral seal, and therefore cause mouth breathing with the associated problems like dry mouth.[9] A device which covers only some of the teeth and leaves others uncovered may potentially have a Dahl effect, leading to undesired movement of the teeth and creating problems like open bite.[9]

Mandibular advancement splints (mandibular repositioning splints) push the lower jaw forwards. The tongue has muscular connections to the mandible and therefore is pulled forwards at the same time, which prevents obstruction of the airway at the oropharynx. This is a similar mechanism to the jaw-thrust maneuver used to maintain patency of a supine patient in first aid. In addition, mandibular advancement splints increase the tension in the soft palate and pharyngeal walls.[9] Mandibular advancement splints are used for snoring and for mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea.[9] They may be useful for people with retrognathia (receded lower jaw).[10]

Tongue repositioning (retaining) devices are made of soft acrylic and cover the upper and lower teeth and create a seal with the lips. They have a "bulb" or "bubble" which sticks out the front of the mouth. This creates negative suction pressure, holding the tongue in a forward position and increasing the airway space behind the tongue.[9] Soft-palate lifters are device which lift the soft palate. They are useful for people who have weak muscles in the region.[9]

Orthodontic treatment

[edit]Orthodontic treatment may improve some dental problems associated with snoring,[4] such as a narrow palate.

Positive airway pressure

[edit]Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is a machine which pumps air through a flexible hose to a mask worn over the mouth, nose, or both. The pressure of the air keeps the airway open. CPAP is considered the gold standard treatment for obstructive sleep apnea.[20] It has been shown to reduce snoring associated with obstructive sleep apnea.[20] However, CPAP can be uncomfortable, and many people stop using it. This is especially true for primary snoring.[20]

Surgery

[edit]Many different surgical procedures are used for snoring, including:

- Nasal surgeries,[9] e.g. septoplasty, various procedures for nasal valve collapse (spreader grafts, spreader flaps, butterfly grafts, batten grafts).[12]

- Palatal surgeries,[9] e.g. uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (most commonly performed procedure for snoring),[10] palatal implants (pillar procedure), somnoplasty (may combine other sites)

- Adenoidectomy or tonsillectomy (or combined, termed adenotonsillectomy).[4]

- Tongue base surgeries[9]

- Hypopharyngeal surgery[9]

- Orthognathic surgery, e.g. maxillary mandibular advancement[9]

- Hypoglossal nerve stimulation[9]

- Tracheostomy[9]

- Bariatric surgery[9]

Epidemiology

[edit]Snoring is one of the most common sleep disorders.[21] The reported prevalence of snoring varies significantly depending on the population studied.[20] Occasional snoring is almost universally present in humans. Habitual (primary snoring) is less common but still a common problem.[6] Snoring affects 2.6–83% of males and 1.5–71% of females.[20]

Snoring is more common in males than females.[6] The reason for this is thought to be the different way fat is distributed in males and females, and also that the upper airway is longer and more collapsible in males.[6] Snoring is more common in older people.[20] Snoring also has positive correlations with larger body-mass index, lower socio-economic status and more frequent smoking and alcohol consumption.[18]

Snoring affects about 8–12% of children.[4]

Society and culture

[edit]There are descriptions of snoring in the fifteenth century.[3] Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty was first used for snoring in 1976.[9] CPAP was first used for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea in 1981.[9] Compared to obstructive sleep apnea, primary snoring has received less attention in research.[20]

Snoring is sometimes not considered as a medical condition by medical insurance companies, meaning that treatments may not be covered by insurance.[3]

"Zzz" is a common onomatopeic representation of snoring. It may have developed from use in comics.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Sateia M, ed. (2014). International Classification of Sleep Disorders (3rd ed.). American Academy of Sleep Medicine. pp. 139–140. ISBN 978-0-9915434-1-0.

- ^ a b c d e f De Meyer M, Jacquet W, Vanderveken OM, Marks L (June 2019). "Systematic review of the different aspects of primary snoring" (PDF). Sleep Medicine Reviews. 45: 88–94. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2019.03.001. PMID 30978609.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Yaremchuk K (June 2020). "Why and When to Treat Snoring". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 53 (3): 351–365. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2020.02.011. PMID 32336469.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Chawla J, Waters KA (September 2015). "Snoring in children". Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 51 (9): 847–50, quiz 850-1. doi:10.1111/jpc.12976. PMID 26333074.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Huang Z, Zhou N, Chattrattrai T, van Selms M, de Vries R, Hilgevoord A, de Vries N, Aarab G, Lobbezoo F (May 2023). "Associations between snoring and dental sleep conditions: A systematic review". Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 50 (5): 416–428. doi:10.1111/joor.13422. hdl:10067/1942640151162165141. PMID 36691754.

- ^ a b c d Chang JL, Goldberg AN, Alt JA, Mohammed A, Ashbrook L, Auckley D, Ayappa I, Bakhtiar H, Barrera JE, Bartley BL, Billings ME, Boon MS, Bosschieter P, Braverman I, Brodie K, Cabrera-Muffly C, Caesar R, Cahali MB, Cai Y, Cao M, Capasso R, Caples SM, Chahine LM, Chang CP, Chang KW, Chaudhary N, Cheong C, Chowdhuri S, Cistulli PA, Claman D, Collen J, Coughlin KC, Creamer J, Davis EM, Dupuy-McCauley KL, Durr ML, Dutt M, Ali ME, Elkassabany NM, Epstein LJ, Fiala JA, Freedman N, Gill K, Gillespie MB, Golisch L, Gooneratne N, Gottlieb DJ, Green KK, Gulati A, Gurubhagavatula I, Hayward N, Hoff PT, Hoffmann O, Holfinger SJ, Hsia J, Huntley C, Huoh KC, Huyett P, Inala S, Ishman SL, Jella TK, Jobanputra AM, Johnson AP, Junna MR, Kado JT, Kaffenberger TM, Kapur VK, Kezirian EJ, Khan M, Kirsch DB, Kominsky A, Kryger M, Krystal AD, Kushida CA, Kuzniar TJ, Lam DJ, Lettieri CJ, Lim DC, Lin HC, Liu S, MacKay SG, Magalang UJ, Malhotra A, Mansukhani MP, Maurer JT, May AM, Mitchell RB, Mokhlesi B, Mullins AE, Nada EM, Naik S, Nokes B, Olson MD, Pack AI, Pang EB, Pang KP, Patil SP, Van de Perck E, Piccirillo JF, Pien GW, Piper AJ, Plawecki A, Quigg M, Ravesloot M, Redline S, Rotenberg BW, Ryden A, Sarmiento KF, Sbeih F, Schell AE, Schmickl CN, Schotland HM, Schwab RJ, Seo J, Shah N, Shelgikar AV, Shochat I, Soose RJ, Steele TO, Stephens E, Stepnowsky C, Strohl KP, Sutherland K, Suurna MV, Thaler E, Thapa S, Vanderveken OM, de Vries N, Weaver EM, Weir ID, Wolfe LF, Woodson BT, Won C, Xu J, Yalamanchi P, Yaremchuk K, Yeghiazarians Y, Yu JL, Zeidler M, Rosen IM (July 2023). "International Consensus Statement on Obstructive Sleep Apnea". International forum of allergy & rhinology. 13 (7): 1061–1482. doi:10.1002/alr.23079. PMC 10359192. PMID 36068685.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Yap YY (March 2022). "Evaluation and Management of Snoring". Sleep Medicine Clinics. 17 (1): 25–39. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2021.10.010. PMID 35216759.

- ^ Chokroverty S (2007). 100 Questions & Answers About Sleep And Sleep Disorders. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 124. ISBN 978-0763741204.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Deenadayal DS, Bommakanti V (4 January 2022). Management of Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Practical Guide. Springer Nature. pp. 1, 4, 14, 29, 34, 44, 50, 51, 55, 56, 64, 98. ISBN 978-981-16-6620-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Dhingra PL, Dhingra S (7 October 2017). Diseases of Ear, Nose and Throat & Head and Neck Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 313. ISBN 978-81-312-4939-0.

- ^ Kiyohara N, Badger C, Tjoa T, Wong B (1 September 2016). "A Comparison of Over-the-Counter Mechanical Nasal Dilators: A Systematic Review". JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery. 18 (5): 385–9. doi:10.1001/jamafacial.2016.0291. PMID 27367589.

- ^ a b c d Casale M, Moffa A, Giorgi L, Pierri M, Lugo R, Jacobowitz O, Baptista P (22 June 2023). "Could the use of a new novel bipolar radiofrequency device (Aerin) improve nasal valve collapse? A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of otolaryngology - head & neck surgery = le Journal d'oto-rhino-laryngologie et de chirurgie cervico-faciale. 52 (1): 42. doi:10.1186/s40463-023-00644-7. PMC 10286448. PMID 37349806.

- ^ Sakarya EU, Bayar Muluk N, Sakalar EG, Senturk M, Aricigil M, Bafaqeeh SA, Cingi C (May 2017). "Use of intranasal corticosteroids in adenotonsillar hypertrophy". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 131 (5): 384–390. doi:10.1017/S0022215117000408. PMID 28238295.

- ^ a b Pacheco MC, Casagrande CF, Teixeira LP, Finck NS, de Araújo MT (July 2015). "Guidelines proposal for clinical recognition of mouth breathing children". Dental Press Journal of Orthodontics. 20 (4): 39–44. doi:10.1590/2176-9451.20.4.039-044.oar. PMC 4593528. PMID 26352843.

- ^ "Snoring Causes". Mayo Clinic. 26 April 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ a b Arab A, Rafie N, Amani R, Shirani F (January 2023). "The Role of Magnesium in Sleep Health: a Systematic Review of Available Literature". Biological Trace Element Research. 201 (1): 121–128. Bibcode:2023BTER..201..121A. doi:10.1007/s12011-022-03162-1. PMID 35184264.

- ^ a b Jung E, Romero R, Yeo L, Gomez-Lopez N, Chaemsaithong P, Jaovisidha A, Gotsch F, Erez O (February 2022). "The etiology of preeclampsia". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 226 (2S): S844 – S866. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2021.11.1356. PMC 8988238. PMID 35177222.

- ^ a b Campos AI, García-Marín LM, Byrne EM, Martin NG, Cuéllar-Partida G, Rentería ME (February 2020). "Insights into the aetiology of snoring from observational and genetic investigations in the UK Biobank". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 817. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11..817C. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-14625-1. PMC 7021827. PMID 32060260.

- ^ Campos AI, Ingold N, Huang Y, Mitchell BL, Kho PF, Han X, García-Marín LM, Ong JS, 23andMe Research Team, Law MH, Yokoyama JS, Martin NG, Dong X, Cuellar-Partida G, MacGregor S, Aslibekyan S, Rentería ME (9 March 2023). "Discovery of genomic loci associated with sleep apnea risk through multi-trait GWAS analysis with snoring". Sleep. 46 (3). doi:10.1093/sleep/zsac308. PMC 9995783. PMID 36525587.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Changsiripun C, Chirakalwasan N, Dias S, McDaid C (October 2024). "Management of primary snoring in adults: A scoping review examining interventions, outcomes and instruments used to assess clinical effects" (PDF). Sleep Medicine Reviews. 77: 101963. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2024.101963. PMID 38889620.

- ^ a b c d e f Bai J, He B, Wang N, Chen Y, Liu J, Wang H, Liu D (2021). "Snoring Is Associated With Increased Risk of Stroke: A Cumulative Meta-Analysis". Frontiers in Neurology. 12: 574649. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.574649. PMC 8047148. PMID 33868139.

- ^ Alam II (15 December 2022). "How to Stop Snoring: Causes, Cures, and Remedies". Medical-Reference. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ "Obstructive sleep apnea: Overview". U.S. National Library of Medicine — Pubmed Health. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Rueda JR, Mugueta-Aguinaga I, Vilaró J, Rueda-Etxebarria M (3 November 2020). "Myofunctional therapy (oropharyngeal exercises) for obstructive sleep apnoea". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (11): CD013449. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013449.pub2. PMC 8094400. PMID 33141943.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Camacho M, Guilleminault C, Wei JM, Song SA, Noller MW, Reckley LK, et al. (April 2018). "Oropharyngeal and tongue exercises (myofunctional therapy) for snoring: a systematic review and meta-analysis". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 275 (4): 849–855. doi:10.1007/s00405-017-4848-5. PMID 29275425. S2CID 3679407.