Slavery in colonial Spanish America

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Lots of word salad. POV issues sugar coating enslavement. More needs to be said about genocide, forced conversion, and extermination of indigenous peoples. Also needs more sources! (October 2024) |

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| European colonization of the Americas |

|---|

|

|

|

Slavery in the Spanish American viceroyalties included indigenous peoples, enslaved people from Africa, and enslaved people from Asia. The economic and social institution of slavery existed throughout the Spanish Empire including Spain itself. Enslaved Africans were brought over to the continent for their labour, indigenous people were enslaved until the 1543 laws that prohibited it.

The Spanish empire enslaved people of African origin. The Spanish often depended on others to obtain enslaved Africans and transport them across the Atlantic.[1][2] Spanish colonies were major recipients of enslaved Africans, with around 22% of the Africans delivered to American shores ending up in the Spanish Empire.[3] Asian people (chinos) in colonial Mexico were also taken from the Philippines and enslaved. They were taken to Acapulco by Novohispanic ships and sold.[4]

The Spanish restricted and outright forbade the enslavement of Native Americans from the early years of the Spanish Empire with the Laws of Burgos of 1512 and the New Laws of 1542.[citation needed] The latter led to the abolition of the Encomienda, private grants of groups of Native Americans to individual Spaniards as well as to Native American nobility.[5] The implementation of the New Laws and liberation of tens of thousands of Native Americans led to a number of rebellions and conspiracies by "Encomenderos" (Encomienda holders) which had to be put down by the Spanish crown.[6]

People were in enslaved in what is now Spain since the times of the Roman Empire. Slavery also existed among Native Americans of both Meso-America and South America. The Crown attempted to limit the bondage of indigenous people, rejecting forms of slavery based on race. Conquistadors regarded indigenous forced labor and tribute as rewards for participation in the conquest and the Crown gave some conquerors encomiendas. The indigenous people held in encomienda were not slaves, but their underpaid labor was mandatory and coerced, while they had rights and could take to trial to their managers,[6] and they were "cared for" by the person in whose charge they were placed (encomendado), this might mean offering them the Christian religion and other perceived (by the Spaniards) benefits of Christian civilization. With the collapse of indigenous populations in the Caribbean, where Spaniards created permanent settlements starting in 1493, Spaniards raided other islands and the mainland for indigenous people to enslave on Hispaniola. With the rise of sugar cultivation as an export product in 1810, Spaniards increasingly utilized enslaved African people for labor on commercial plantations.[7] Although plantation slavery in Spanish America was one aspect of slave labor, urban slavery in households, religious institutions, textile workshops (obrajes), and other venues was also important.[8]

Spanish slavery in the Americas diverged from other European powers in that it took on an early abolitionist stance towards Native American slavery. Although it did not directly partake in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, enslaved Black people were sold throughout the Spanish Empire, particularly in Caribbean territories.[9] During the colonial period, Spanish territories were the most extensive and wealthiest in the Americas. Since Spaniards themselves were barred by the Crown from participating in the Atlantic slave trade, the right to export slaves in these territories, known as the Asiento de Negros was a major foreign policy objective of other European powers, sparking numerous European wars such as the War of Spanish Succession and the War of Jenkins' Ear. In the mid-nineteenth century when most countries in the Americas reformed to disallow chattel slavery, Cuba and Puerto Rico – the last two remaining Spanish American colonies – were among the last, followed only by Brazil.[a][10]

Enslaved people challenged their captivity in ways that ranged from introducing non-European elements into Christianity (syncretism) to mounting alternative societies outside the plantation (slave labour camp) system (Maroons). The first open Black rebellion occurred in Spanish labour camps (plantations) in 1521.[11] Resistance, particularly to the enslavement of indigenous people, also came from Spanish religious and legal ranks.[12] The first speech in the Americas for the universality of human rights and against the abuses of slavery was also given on Hispaniola, a mere nineteen years after the first contact.[13] Resistance to indigenous captivity in the Spanish colonies produced the first modern debates over the legitimacy of slavery.[b] And uniquely in the Spanish American colonies, laws like the New Laws of 1542, were enacted early in the colonial period to protect natives from bondage.[14][15] To complicate matters further, Spain's haphazard grip on its extensive American dominions and its erratic economy acted to impede the broad and systematic spread of plantations operated by slave labor. Altogether, the struggle against slavery in the Spanish American colonies left a notable tradition of opposition that set the stage for conversations about human rights.[16]

Background

[edit]

Slavery in Spain traces back to the times of the Greeks, Phoenicians and Romans. Slavery was cross-cultural and multi-ethnic, and had an important role in the development of European economies such as Spain.[17] The Romans extensively utilized slaves according to the Code of Justinian. Following the rise of Christianity, Christians were in theory barred from enslaving their fellow Christians, but the practice persisted. With the rise of Islam, and the conquest of most of the Iberian peninsula in the eighth century, slavery declined in the remaining Christian kingdoms of Iberia.[18]

At the formation of Al-Andalus, Muslims were prohibited from enslaving other Muslims, but non-Muslim Spanish and Eastern European slaves were traded by Muslims and local Jewish merchants. Mozarabs and Jews were allowed to remain and retain their slaves if they paid a head tax for themselves and half-value for the slaves, but non-Muslims were prohibited from holding Muslim slaves. If one of their slaves converted to Islam, they were required to sell the slave to a Muslim. Mozarabs were later, by the 9th and 10th centuries, permitted to purchase new non-Muslim slaves via the peninsula's established slave trade.[19]

During the reconquista, Christian Spain sought to retake territory lost to Muslims, leading to changing norms regarding slavery. Though enslavement of Christians was originally permitted, the Christian kingdoms gradually ceased this practice between the 8th and 11th centuries, limiting their pool of slaves to Al-Andalusian Muslims. The enslavement of conquered Muslims was supposedly justified on the basis of conversion and acculturation, but Muslim captives were often offered back to their families and communities for cash payments (rescate). The thirteenth-century code of law, the Siete Partidas of Alfonso X of Castile (1252–1284), specified slaves' good treatment by their masters, and who could be enslaved: those who were captured in just war; offspring of an enslaved mother; those who voluntarily sold themselves into slavery. This was generally domestic slavery and was a temporary condition for members of outgroups.[20] The Siete Partidas described slavery as "the basest and most wretched condition into which anyone could fall because man, who is the freest noble of all God's creatures, becomes thereby in the power of another, who can do with him what he wishes as with any property, whether living or dead."[21]

As the Spanish (Castilians) and Portuguese expanded overseas, they conquered and occupied Atlantic islands off the north coast of Africa—including the Canary Islands, São Tomé and Madeira—where they introduced sugar plantations.[22] In the Canary Islands, the Spanish practised the encomienda system, a type of forced labor modelled on the reconquista practice of awarding Muslim laborers to Christian victors.[23] The Spanish treated the Canarian natives, known as the Guanches, as pagans, but several attempts were made by the Catholic Church to prevent their enslavement and defend the freedom of evangelized Canarians.[24] Despite this, the Guanches' population precipitously declined as a result of encomienda.[25]

Under Castilian control, in the period from 1498 (when the Catholic Kings ordered the freedom of the Guanches) until 1520 (when the last Guanches were freed), Guanche encomienda was replaced by African chattel slavery. Castilians traded a variety of European goods—including firearms and horses—for slaves from West Africa, where the existing slave trade had begun to shift to the coast to meet European demand.[26][27] In these colonies off the coast of Africa, the Spanish engaged in sugar cane production following the model of Mediterranean production. The sugar complex consisted of slave labor for cultivation and processing, with the sugar mill (ingenio) and equipment established with significant investor capital. When plantation slavery was established in Spanish America and Brazil, they replicated the elements of the complex in the New World on a much larger scale.[28] In the Spanish colonies of the New World, the encomienda system would also be revived to enslave indigenous peoples. This system became much more widespread following the Spanish contact and conquests in Mexico and Peru, but the precedents had been set prior to 1492, in the Canary Islands.[29]

Indigenous slavery

[edit]

Some Indigenous peoples of the Americas, such as the Aztec and Inca Empires, practised their own forms of slavery and unfree labor prior to the arrival of the Spanish. The Spanish conquest and settlement in the New World quickly led to large-scale subjugation of indigenous peoples, mainly of the Native Caribbean people, by Columbus on his four voyages. Initially, forced labor represented a means by which the conquistadores mobilized native labor, with disastrous effects on the population. Unlike the Portuguese Crown's support for the slave trade in Africa, los Reyes Católicos (English: Catholic Monarchs) opposed the enslavement of the native peoples in the newly conquered lands on religious grounds. When Columbus returned with indigenous slaves, they ordered the survivors to be returned to their homelands. In 1512, after pressure from Dominican friars, the Laws of Burgos were introduced to protect the rights of the Natives in the New World and secure their freedom. The papal bull Sublimus Dei of 1537, to which Spain was committed, also officially banned enslavement of indigenous peoples, but it was rescinded a year after its promulgation.[citation needed]

When Ponce de León and the Spaniards arrived on the island of Borikén (Puerto Rico), they enslaved Taíno tribes on the island, forcing them to work in the gold mines and in the construction of forts. Many Taíno died, particularly from smallpox, to which they had no immunity. Other Taínos committed suicide or left the island after the failed Taíno revolt of 1511.[citation needed] The Spanish colonists, fearing the loss of their labour force, complained to the courts that they needed manpower. As an alternative, Las Casas suggested the importation and use of African slaves. In 1517, the Spanish Crown permitted its subjects to import twelve slaves each, thereby beginning the slave trade on the colonies.[30]

Encomienda system

[edit]In the New World, the Crown granted conquistadores the right to extract labour and tribute from natives who were under Spanish rule.[31] [32] This encomienda system was established on the island of Hispaniola by Nicolás de Ovando, the third governor of the Spanish colony, in 1502. Some women and some indigenous elites—such as Maria Jaramillo, the daughter of Marina and conqueror Juan Jaramillo—were also owners to these contracts (or encomenderos).[33]

In most of the Spanish domains acquired in the 16th century, the encomienda phenomenon lasted only a few decades. In Peru and New Spain, the encomienda institution lasted much longer.[34] Spanish colonist turned Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas (1484–1566), who observed and recorded the effects of enslavement on the Native populations, campaigned for protections of the indigenous population, especially crown limits on the exploitation of the encomienda, helping to bring about the 1542 New Laws which would replace encomienda with repartimiento.[35][36]

In New Spain, the collapse of indigenous populations from conquest and disease led to a shift from the encomienda system to pueblos de indios—the encomienda system no longer made economic sense as there were not enough Amerindians remaining. This consolidated labor in a process known as reducciones, and replaced encomienda with "two parallel yet separate 'republics'":[37] the república de españoles "included Spaniards, who lived in Spanish cities and obeyed Spanish law"; and the república de indios "included natives, who resided in native communities, where native law and native authorities (as long as they did not contradict Spanish norms) prevailed".[37] The Amerindians who lived in the pueblos de indios had ownership over their land, but, because they were deemed subjects of the Spanish Crown, had to pay tribute.[38]

The replacement of encomienda with repartimiento caused considerable anger among the conquistadors, who had expected to hold their grants to hold indigenous slaves in perpetuity.[39][40][41] In Chiloé Archipelago in southern Chile, where the abuse of encomienda had led to the Huilliche uprising of 1712, the encomienda was only abolished in 1782.[42] In the rest of Chile it was abolished in 1789, and in the whole Spanish empire in 1791.[42][43][44][45]

Repartimiento system

[edit]After passage of the New Laws in 1542, also known as the New Laws of the Indies for the Good Treatment and Preservation of the Indians, the Spanish greatly restricted the power of the encomienda system, which had allowed abuse by holders of the labor grants (encomenderos), and officially abolished the enslavement of the native population except in certain circumstances. The encomienda system was replaced by the repartimiento system.[39][46][47]

With the repartimiento system, the Spanish Crown aimed to remove control of the indigenous population, now considered its subjects, from the hands of the encomenderos, who had become a politically influential and wealthy class.[48] The repartimiento system was not considered slavery—since the worker was not owned outright, was free in various respects other than in the dispensation of their labor, and the work was intermittent—but it created slavery-like conditions in certain areas, most notoriously in silver mines of the 16th century Viceroyalty of Peru under the draft labor system known as mita, which was partially influenced by a similar draft labor system the Inca used also called mit'a.[48][49]

The repartimiento system allocated a number of Native workers to the Crown who were then assigned to work for Spanish settlers for a set period of time, usually several weeks, through a local Crown official. This was intended to reduce the abuses associated with encomienda.[47] In practice, the process was overseen by a conquistador, or later a Spanish settler or official, and applications for laborers were submitted to a district magistrate or special judge. Legally, these systems were not allowed to interfere with the Amerindians' own survival, with only 7-10% of the indigenous adult male population allowed to be assigned at any time.[50] The Amerindians were paid wages, which they could then use to pay tribute to the Crown.[51] Native men, working around three to four weeks a year, could also be allocated to public works such as harvests, mines, and infrastructure. Mining, specifically, was a concern for the Crown as well as the Peruvian viceroy. While there were attempts to guard against overwork, abuses of power and high quotas set by mine owners continued, leading to both depopulation and the system of indigenous men buying themselves out of the labor draft by paying their own curacas or employers.[48][52]

Enslavement of rebels

[edit]

Despite the abolition of the encomienda system, indigenous people who rebelled against the Spanish could still be enslaved. Following the Mixtón War (1540–42) in northwest Mexico, many indigenous slaves were captured and relocated. The statutes of 1573, within the "Ordinances Concerning Discoveries", forbade unauthorized operations against independent Indian peoples.[46] It required appointment of a protector de indios, an ecclesiastical representative who acted as the protector of the Indians and represented them in formal litigation.[53][54]

Reinstatement of slavery for Mapuche rebels

[edit]King Philip III inherited a difficult situation in colonial Chile, where the Arauco War raged and the local Mapuche succeeded in razing seven Spanish cities (1598–1604). An estimate by Alonso González de Nájera put the toll at 3000 Spanish settlers killed and 500 Spanish women taken into captivity by Mapuche.[55] In retaliation, the proscription against enslaving Indians captured in war was lifted by Philip in 1608.[56][57] Spanish settlers in Chiloé Archipelago abused the decree to launch slave raids against groups such as the Chono people of northwestern Patagonia, who had never been under Spanish rule and never rebelled.[58] The Real Audiencia of Santiago said in the 1650s that Mapuche slavery was one of the reasons for the constant state of war between the Spanish and the Mapuche.[59] Enslavement of Mapuches "caught in war" was abolished in 1683 after decades of legal attempts by the Spanish Crown to suppress it.[57]

Black slavery

[edit]

When Spain first enslaved Native Americans on Hispaniola, and then replaced them with captive Africans, it established slave labor as the basis for colonial sugar production. Europeans believed that Africans had developed immunities to European diseases, and would not be as susceptible to illness as the Native Americans because they had not been exposed to the pathogens yet.[60]

With the increased dependency on enslaved Africans and with the Spanish crown opposed to the enslavement of indigenous people, except in the case of rebellion, slavery became associated with race and racial hierarchy, with Europeans hardening their concepts of racial ideologies. These were buttressed by prior ideologies of differentiation as that of the limpieza de sangre (en: purity of blood), which in Spain referred to individuals without the perceived taint of Jewish or Muslim ancestry.[61] In Spanish America, purity of blood came to mean a person free of any African ancestry.[62]

In the vocabulary of the time, each enslaved African who arrived at the Americas was called "Pieza de Indias" (en: a piece of the Indies). The crown issued licenses or "asientos" to merchants, regulating the trade in slaves. During the 16th century, the Spanish colonies were the most important customers of the Atlantic slave trade, purchasing thousands of slaves directly from the Portuguese, but other European nations soon dwarfed these numbers when their demand for enslaved workers began to drive the slave market to unprecedented levels.[39]

Black slavery in the early colonial period

[edit]

In 1501, Spanish colonists began importing enslaved Africans from the Iberian Peninsula to their Santo Domingo colony on the island of Hispaniola. These first Africans, who had been enslaved in Europe before crossing the Atlantic, may have spoken Spanish and perhaps were even Christians. About 17 of them started in the copper mines, and about a hundred were sent to extract gold. As Old World diseases decimated Caribbean indigenous populations in the first decades of the 1500s, enslaved Africans (bozales) gradually replaced their labor, but they also mingled and joined with indigenous groups in flights to freedom, creating mixed-race maroon communities in all the islands where Europeans had established chattel slavery.[63] In Spanish Florida and farther north, the first African slaves arrived in 1526 with Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón's establishment of San Miguel de Gualdape on the current Georgia coast.[64] [65] They rebelled and lived with indigenous people, destroying the colony in less than two months.[66] More slaves arrived in Florida in 1539 with Hernando de Soto, and in 1565 with the founding of St. Augustine, Florida.[65][66]

In Mexico City in 1537, a number of blacks were accused of rebellion. They were executed in the main plaza (zócalo) by hanging, an event recorded in an indigenous manuscript.[67] Slaves escaping to Florida from the colony of Georgia were offered their freedom by Carlos II's proclamation November 7, 1693, on condition of converting to Catholicism,[68] and it became a place of refuge for slaves fleeing the Thirteen Colonies.[68][69]

By 1570, the colonists in Puerto Rico found the gold mines were depleted, relegating the island to a garrison for passing ships. The cultivation of crops such as tobacco, cotton, cocoa, and ginger became increasingly important to the economy.[70] With rising demand for sugar on the international market, major planters increased their labour-intensive cultivation and processing of sugar cane. Sugar plantations supplanted mining as Puerto Rico's main industry and kept demand high for African slavery.[70]

Black slavery in the late colonial period

[edit]The population of slaves in Cuba received a large boost when the British captured Havana during the Seven Years' War, and imported 10,000 slaves from their other colonies in the West Indies to work on newly established agricultural plantations. These slaves were left behind when the British returned Havana to the Spanish as part of the Treaty of Paris (1763), and form a significant part of the Afro-Cuban population today.[71]

Cuba developed two distinct but interrelated sources of sugar production using enslaved labor, which converged at the end of the eighteenth century. The first of these sectors was urban and was directed in large measure by the needs of the Spanish colonial state, reaching its height in the 1760s. As a result, Thomas Kitchin reported in 1778 that "about 52,000 slaves" were being brought from Africa to the West Indies by Europeans, with approximately 4,000 being brought by the Spanish.[72] The second sector, which flourished after 1790, was rural and was directed by private planters involved in the production of export agricultural commodities. After 1763, the scale and urgency of defense projects led the state to deploy many of its enslaved workers in ways that foreshadowed the intense work regimes on sugar plantations in the nineteenth century. Another important group of workers enslaved by the Spanish colonial state in the late eighteenth century were the king's laborers, who worked on the city's fortifications.[citation needed]

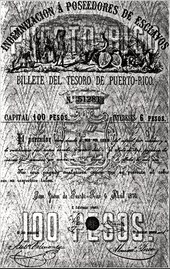

After 1784, Spain provided five ways by which slaves could obtain freedom.[73] Five years later, the Spanish Crown issued the "Royal Decree of Graces of 1789", which set new rules related to the slave trade and added restrictions to the granting of freedman status. The decree granted its subjects the right to purchase slaves and to participate in the slave trade in the Caribbean. Later that year a new slave code, known as El Código Negro (The Black Code), was introduced.[74] Under "El Código Negro", a slave could buy his freedom, in the event that his master was willing to sell, by paying the price sought in installments. Slaves were allowed to earn money during their spare time by working as shoemakers, cleaning clothes, or selling the produce they grew on their own plots of land. For the freedom of their newborn child, not yet baptized, they paid half the going price for a baptized child.[74] Many of these freedmen started settlements in the areas which became known as Cangrejos (Santurce), Carolina, Canóvanas, Loíza, and Luquillo. Some became slave owners themselves.[75] Despite these paths to freedom, from 1790 onwards, the number of slaves more than doubled in Puerto Rico as a result of the dramatic expansion of the sugar industry in the island.[70]

The Spanish colonies in the Caribbean were among the last to abolish slavery. While the British abolished slavery by 1833, Spain abolished slavery in Puerto Rico in 1873. Peru was one of the countries that revived the institution for some decades after declaring independence from Spain in the early 19th century.[citation needed]

Conditions for black slaves

[edit]African slaves were legally branded with a hot iron on the forehead, prevented their "theft" or lawsuits that challenged their captivity.[75] The colonists continued this branding practice for more than 250 years.[73] Enslaved Africans were sent to work in the gold mines, or in the island's ginger and sugar fields. They were allowed to live with their families in a hut on the master's land, and given a patch of land where they could farm, but otherwise were subjected to harsh treatment, including sexual abuse. Many colonists, arriving without women, intermarried with their slaves or with Taínos. Their mixed-race descendants formed the first generations of the early Puerto Rican and Cuban populations.[75]

The slaves had little choice but to adapt. Many converted to Christianity and were given their masters' surnames.[75] Both women and men were subject to the punishments of violence and humiliating abuse. Slaves who misbehaved or disobeyed their masters were often placed in stocks in the depths of the boiler houses where they were abandoned for days at a time, and oftentimes for two to three months. These wooden stocks were made in two types: lying-down or stand-up types. According to Esteban Montejo—a survivor of slavery who was interviewed by Miguel Barnet for his 1966 testimonial narrative Biografía de un cimarrón (Biography of a Runaway Slave)—women were punished even when pregnant. They were subjected to whippings: they had to lie "face down over a scooped-out piece of round [earth] to protect their bellies."[76][better source needed] Some masters reportedly whipped pregnant women in the belly, causing miscarriages. Montejo said the wounds were treated with "compresses of tobacco leaves, urine and salt".[77][better source needed]

Across the Americas, some 70% of slaves worked on sugar plantations and related industries.[78] The slaves who worked on sugar plantations and in sugar mills were often subject to the harshest conditions. The field work was rigorous manual labour which the slaves began at an early age. The work days lasted close to 20 hours during harvest and processing, including cultivating and cutting the crops, hauling wagons, and processing sugarcane with dangerous machinery.[79][77][80] According to Montejo, the slaves were forced to reside in barracoons, where they were crammed in and locked in by a padlock at night, getting about three to four hours of sleep. He described the conditions of the barracoons as harsh, highly unsanitary, extremely hot, and typically unventilated.[81]

Cuba's slavery system was gendered in a way that some duties were performed only by male slaves, some only by female slaves. Female slaves in Havana from the 16th century onwards performed duties such as operating the town taverns, eating houses, and lodges, as well as being laundresses and domestic labourers and servants. Female slaves also served as town prostitutes. Some Cuban women could gain limited freedom by having children with white men. As in other Latin cultures, there were looser borders with the mulatto or mixed-race population. Sometimes men who took slaves as wives or concubines freed both them and their children. As in New Orleans and Saint-Domingue, mulattos began to be classified as a third group between the European colonists and African slaves. Freedmen, generally of mixed race, came to represent 20% of the total Cuban population and 41% of the non-white Cuban population.[82]

The death toll for African slaves was often high, requiring the planters to replace slaves who died under the harsh regime.[83] As well as importing new African slaves, planters encouraged Afro-Cuban slaves to have children in order to reproduce their work force. This became more common as the supply of slaves from Africa slowed due to the increasing popularity of abolitionism.[84] According to Montejo, masters wanted to pair strong and large-built black men with healthy black women. He described slaves being placed in the barracoons and forced to have sex, to provide new "breed stock" from their children, who would sell for around 500 pesos. Montejo said that sometimes, if the overseers did not like the quality of children, they separated the parents and sent the mother back to working in the fields.[83][84]

In 1789 the Spanish Crown led an effort to reform slavery and issued a decree, Código Negro Español (Spanish Black Code), that specified food and clothing provisions, put limits on the number of work hours, limited punishments, required religious instruction, and protected marriages, forbidding the sale of young children away from their mothers. But planters often flouted the laws and protested against them, considering them a threat to their authority and an intrusion into their personal lives.[79] The slaveowners did not protest against all the measures of the codex, many of which they argued were already common practices. They objected to efforts to set limits on their ability to apply physical punishment. For instance, the Black Codex limited whippings to 25 and required the whippings "not to cause serious bruises or bleeding". The slave-owners thought that the slaves would interpret these limits as weaknesses, ultimately leading to resistance. Another contested issue was the work hours that were restricted "from sunrise to sunset"; plantation owners responded by explaining that cutting and processing of cane needed 20-hour days during the harvest season.[79]

Fugitive slaves in Spanish territories

[edit]On May 29, 1680 the Spanish crown decreed that slaves escaping to Spanish territories from Barlovento, Martinique, San Vicente and Granada in the Lesser Antilles would be free if they accepted Catholicism. On September 3, 1680 and June 1, 1685 the crown issued similar decrees for escaping French slaves. On November 7, 1693 King Carlos II issued a decree freeing all slaves escaping from the English colonies who accepted Catholicism. There were similar decrees October 29, 1733, March 11 and November 11, 1740, and September 24, 1850 in the Buen Retiro by Ferdinand VI and the Royal Decree of October 21, 1753.[85]

Since 1687, Spanish Florida attracted numerous African slaves who escaped from slavery in the Thirteen Colonies. Since 1623 the official Spanish policy had been that all slaves who touched Spanish soil and asked for refuge could become free Spanish citizens, and would be assisted in establishing their own workshops if they had a trade or given a grant of land to cultivate if they were farmers. In exchange they would be required to convert to Catholicism and serve for a number of years in the Spanish militia. Most were settled in a community called Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, the first settlement of free Africans in North America. The enslaved African Francisco Menéndez escaped from South Carolina and traveled to St. Augustine, Florida,[86] where he became the leader of the settlers at Mose and commander of the black militia company there from 1726 until sometime after 1742.[87]

The former slaves also found refuge among the Creek and Seminole, Native Americans who had established settlements in Florida at the invitation of the Spanish government.[dubious – discuss] In 1771, Governor of Florida John Moultrie wrote to the Board of Trade, "It has been a practice for a good while past, for negroes to run away from their Masters, and get into the Indian towns, from whence it proved very difficult to get them back."[88] When colonial officials asked the Native Americans to return the fugitive slaves, they replied that they had "merely given hungry people food, and invited the slaveholders to catch the runaways themselves."[88]

After the American Revolutionary War, slaves from the state of Georgia and the Low Country of South Carolina escaped to Florida. The U.S. Army led increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory, including the 1817–1818 campaign by Andrew Jackson that became known as the First Seminole War. The United States afterwards effectively controlled East Florida (from the Atlantic to the Appalachicola River). According to Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, the US had to take action there because Florida had become "a derelict open to the occupancy of every enemy, civilized or savage, of the United States, and serving no other earthly purpose than as a post of annoyance to them.".[89] Spain requested British intervention, but London declined to assist Spain in the negotiations. Some of President James Monroe's cabinet demanded Jackson's immediate dismissal, but Adams realized that Jackson's actions had put the U.S. in a favorable diplomatic position. Adams negotiated very favorable terms.[90]

As Florida had become a burden to Spain, which could not afford to send settlers or garrisons, the Crown decided to cede the territory to the United States. It accomplished this through the Adams–Onís Treaty in 1819, effective 1821.

Ending of slavery

[edit]Support for abolitionism rose in Great Britain. Slavery in France's Caribbean colonies was abolished by Revolutionary decree in 1794, (slavery in Metropolitan France was abolished in 1315 by Louis X) but was restored under Napoleon I in 1802. Slaves in Saint-Domingue revolted in response and became independent following a brutal conflict. The victorious former slaves founded the republic of Haiti in 1804.

Later slave revolts were arguably part of the upsurge of liberal and democratic values centered on individual rights and liberties which came in the aftermath of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution in Europe. As emancipation became more of a concrete reality, the slaves' concept of freedom changed. No longer did they seek to overthrow the whites and re-establish carbon-copy African societies as they had done during the earlier rebellions; the vast majority of slaves were creole, native born where they lived, and envisaged their freedom within the established framework of the existing society.

The Spanish American wars of independence emancipated most of the overseas territories of Spain; in the Americas, various nations emerged from these wars. The wars were influenced by the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment and economic affairs, which also led to the reduction and ending of feudalism. For example, in Mexico on 6 December 1810, Miguel Hidalgo, leader of the independence movement, issued a decree abolishing slavery, threatening those who did not comply with death. In South America Simon Bolivar abolished slavery in the lands that he liberated. However, it was not a unified process. Some countries, including Peru and Ecuador, reintroduced slavery for some time after achieving independence.

The Assembly of Year XIII (1813) of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata declared the freedom of wombs. It did not end slavery completely, but emancipated the children of slaves. Many slaves gained emancipation by joining the armies, either against royalists during the War of Independence, or during the later Civil Wars. For example, the Argentine Confederation ended slavery definitely with the sanction of the Argentine Constitution of 1853.

In the treaty of 1814, King Ferdinand VII of Spain promised to consider means for abolishing the slave trade. In the treaty of September 23, 1817, with Great Britain, the Spanish Crown said that "having never lost sight of a matter so interesting to him and being desirous of hastening the moment of its attainment, he has determined to co-operate with His Britannic Majesty in adopting the cause of humanity." The king bound himself "that the slave trade will be abolished in all the dominions of Spain, May 30, 1820, and that after that date it shall not be lawful for any subject of the crown of Spain to buy slaves or carry on the slave trade upon any part of the coast of Africa." The date of final suppression was October 30. The subjects of the king of Spain were forbidden to carry slaves for any one outside the Spanish dominions, or to use the flag to cover such dealings.[citation needed]

On March 22, 1873, slavery was legally abolished in Puerto Rico. However, slaves were not emancipated but rather had to buy their own freedom, at whatever price was set by their last masters. They were also required to work for another three years for their former masters, for other colonists interested in their services, or for the state in order to pay some compensation.[91] Between 1527 and 1873, slaves in Puerto Rico had carried out more than twenty revolts.[92][93] Slavery in Cuba was abolished by Spanish royal decree on October 7, 1886.

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Las Casas, Bartolomé de, The Devastation of the Indies, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore & London, 1992.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de, History of the Indies, translated by Andrée M. Collard, Harper & Row Publishers, New York, 1971,

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de, In Defense of the Indians, translated by Stafford Poole, C.M., Northern Illinois University, 1974.

Secondary readings

[edit]- Aguirre Beltán, Gonzalo. La población negra de México, 1519-1819: Un estudio etnohistórico. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1972, 1946.

- Aimes, Hubert H. A History of Slavery in Cuba 1511 to 1868, New York, NY : Octagon Books Inc, 1967.

- Bennett, Herman Lee. Africans in Colonial Mexico. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005.

- Blackburn, Robin. The Making of New World Slavery: From the Baroque to the Modern,1492-1800. New York: Verso 1997.

- Blanchard, Peter, Under the flags of freedom : slave soldiers and the wars of independence in Spanish South America. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, c2008.

- Bowser, Frederick. The African Slave in Colonial Peru, 1524-1650. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1974.

- Bush, Barbara. Slave Women in Caribbean Society, London: James Currey Ltd, 1990.

- Carroll, Patrick James. Blacks in Colonial Veracruz: Race, Ethnicity, and Regional Development. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991.

- Curtin, Philip. The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969.

- Davidson, David M. "Negro Slave Control and Resistance in Colonial Mexico, 1519-1650." Hispanic American Historical Review 46 no. 3 (1966): 235–53.

- Diaz Soler, Luis Manuel "Historia De La Esclavitud Negra en Puerto Rico (1950)". LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses

- Ferrer, Ada. Insurgent Cuba: race, nation, and revolution, 1868-1898, Chapel Hill; London: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

- Figueroa, Luis A. Sugar, Slavery, and Freedom in Nineteenth-Century Puerto Rico. University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- Foner, Laura, and Eugene D. Genovese, eds. Slavery in the New World: A Reader in Comparative History. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall, 1969.

- Fuente, Alejandro de la. "Slave Law and Claims Making in Cuba: The Tannenbaum Debate Revisited." Law and History Review (2004): 339–69.

- Fuente, Alejandro de la. "From Slaves to Citizens? Tannenbaum and the Debates on Slavery, Emancipation, and Race Relations in Latin America," International Labor and Working-Class History 77 no. 1 (2010), 154–73.

- Fuente, Alejandro de la. "Slaves and the Creation of Legal Rights in Cuba: Coartación and Papel", Hispanic American Historical Review 87, no. 4 (2007): 659–92.

- García Añoveros, Jesús María. El pensamiento y los argumentos sobre la esclavitud en Europa en el siglo XVI y su aplicación a los indios americanos y a lost negros africanos. Corpus Hispanorum de Pace. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2000.

- Geggus, David Patrick. "Slave Resistance in the Spanish Caribbean in the Mid-1790s," in A Turbulent Time: The French Revolution and the Greater Caribbean, David Barry Gaspar and David Patrick Geggus. Bloomington: Indiana University Press 1997, pp. 130–55.

- Gibbings, Julie. "In the Shadow of Slavery: Historical Time, Labor, and Citizenship in Nineteenth-Century Alta Verapaz, Guatemala", Hispanic American Historical Review 96.1, (February 2016): 73–107.

- Grandin, Greg. The Empire of Necessity: Slavery, Freedom, and Deception in the New World, Macmillan, 2014.

- Gunst, Laurie. "Bartolomé de las Casas and the Question of Negro Slavery in the Early Spanish Indies." PhD dissertation, Harvard University 1982.

- Helg, Aline, Liberty and Equality in Caribbean Colombia, 1770-1835. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

- Heuman, Gad, and Trevor Graeme Burnard, eds. The Routledge History of Slavery. New York: Taylor and Francis, 2011.

- Hünefeldt, Christine. Paying the Price of Freedom: Family and Labor among Lima's Slaves, 1800-1854. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1994.

- Johnson, Lyman L. "Manumission in Colonial Buenos Aires, 1776-1810." Hispanic American Historical Review 59, no. 2 (1979): 258-79.

- Johnson, Lyman L. "A Lack of Legitimate Obedience and Respect: Slaves and Their Masters in the Courts of Late Colonial Buenos Aires," Hispanic American Historical Review 87, no. 4 (2007), 631–57.

- Klein, Herbert S. The Middle Passage: Comparative Studies in the Atlantic Slave Trade. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978.

- Klein, Herbert S., and Ben Vinson III. African Slavery in Latin America and the Caribbean. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Landers, Jane. Black Society in Spanish Florida. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

- Landers, Jane and Barry Robinson, eds. Slaves, Subjects, and Subversives: Blacks in Colonial Latin America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

- Lockhart, James. Spanish Peru, 1532–1560: A Colonial Society. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968.

- Love, Edgar F. "Negro Resistance to Spanish Rule in Colonial Mexico," Journal of Negro History 52, no. 2 (April 1967), 89–103.

- Mondragón Barrios, Lourdes. Esclavos africanos en la Ciudad de México: el servicio doméstico durante el siglo XVI. Mexico: Ediciones Euroamericanas, 1999.

- O'Toole, Rachel Sarah. Bound Lives: Africans, Indians, and the Making of Race in Colonial Peru. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 2012.

- Montejo, Esteban (2016). Barnet, Miguel (ed.). Biography of a Runaway Slave: Fiftieth Anniversary Edition. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-8101-3342-6.

- Palacios Preciado, Jorge. La trata de negros por Cartagena de Indias, 1650-1750. Tunja: Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, 1973.

- Palmer, Colin. Slaves of the White God: Blacks in Mexico, 1570-1650. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- Palmer, Colin. Human Cargoes: The British Slave Trade to Spanish America, 1700-1739. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981.

- Proctor, Frank T., III "Damned Notions of Liberty": Slavery, Culture and Power in Colonial Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2010.

- Proctor III, Frank T. "Gender and Manumission of Slaves in New Spain," Hispanic American Historical Review 86, no. 2 (2006), 309–36.

- Resendez, Andres (2016). The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 448. ISBN 978-0544602670.

- Restall, Matthew, and Jane Landers, "The African Experience in Early Spanish America," The Americas 57, no. 2 (2000), 167–70.

- Rout, Leslie B. The African Experience in Spanish America, 1502 to the Present Day. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- Seijas, Tatiana. Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico: From Chinos to Indians. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Sharp, William Frederick. Slavery on the Spanish Frontier: The Colombian Chocó, 1680-1810. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976.

- Sierra Silva, Pablo Miguel. Urban Slavery in Colonial Mexico: Puebla de los Angeles, 1531-1706. New York: Cambridge University Press 2018.

- Shepherd, Verene A., ed. Slavery Without Sugar. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2002. Print.

- Solow, Barard I. ed., Slavery and the Rise of the Atlantic System. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Tannenbaum, Frank. Slave and Citizen: The Negro in the Americas. New York Vintage Books, 1947.

- Toplin, Robert Brent. Slavery and Race Relations in Latin America. Westport CT: Greenwood Press, 1974.

- Vinson, Ben, III, and Matthew Restall, eds. Black Mexico: Race and Society from Colonial to Modern Times. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2009.

- Walker, Tamara J. "He Outfitted His Family in Notable Decency: Slavery, Honour, and Dress in Eighteenth-Century Lima, Peru," Slavery & Abolition 30, no. 3 (2009), 383–402.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Differently from Puerto Rico, which abolished slavery definitely in 1873, chattel slavery, in one way or another, remained legal in Cuba and Brazil until the 1880s. A series of legal procedures (e.g., Moret Law) and apprenticeships imposed on those supposedly freed, delayed the complete abolition of slavery. Meanwhile, slavery was gradually replaced with peonage and the harsh use of Asian migrant workers. See, Ferrer, Insurgent Cuba, UNC, 1999, p 18.

- ^ In 2007, Castro challenged the position of Bartolomé de las Casas as a central human-rights figure: "rather than viewing him as the ultimate champion of indigenous causes, we must see the Dominican friar as the incarnation of a more benevolent, paternalistic form of ecclesiastical, political, cultural and economic imperialism rather than as a unique paradigmatic figure". See: Castro, The Other Face, Duke, 2007, p 8.

External links

[edit]- African Laborers for a New Empire: Iberia, Slavery, and the Atlantic World (Lowcountry Digital Library)

- First Blacks in the Americas: the African presence in the Dominican Republic (CUNY Dominican Studies Institute)

- North American Slavery in the Spanish and English colonies(Mission San Luis)

- Slavery Contract (PortCities UK)

- Slavery and Spanish Colonization (University of Houston, Digital History)

References

[edit]- ^ "Map: Countries and broad regions of the Atlantic world where slave voyages were organised". www.slavevoyages.org.

- ^ "The Early Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade: Emperor Charles V · African Laborers for a New Empire: Iberia, Slavery, and the Atlantic World · Lowcountry Digital History Initiative". College of Charleston. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ "Slavery and Atlantic slave trade facts and figures".

- ^ Seijas, Tatiana.Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico: From Chinos to Indians. New York: Cambridge University Press 2014.[page needed]

- ^ Suárez Romero, Miguel Ángel (11 August 2017). "La Situación Jurídica del Indio Durante la Conquista Española en América". Revista de la Facultad de Derecho de México. 54 (242): 229. doi:10.22201/fder.24488933e.2004.242.61367.

- ^ a b Yeager, Timothy J. (December 1995). "Encomienda or Slavery? The Spanish Crown's Choice of Labor Organization in Sixteenth-Century Spanish America". The Journal of Economic History. 55 (4): 842–859. doi:10.1017/S0022050700042182. S2CID 155030781.

- ^ Blackburn, Robin. The Making of New World Slavery: From the Baroque to the Modern, 1492-1800. New York: Verso 1997, 137-43

- ^ Sierra Silva, Pablo Miguel.Urban Slavery in Colonial Puebla de los Ángeles, 1531-1706. New York: Cambridge University Press 2018.

- ^ Fradera, Josep M.; Schmidt-Nowara, Christopher (2013). "Introduction". Slavery and Antislavery in Spain's Atlantic Empire. Berghahn Books. pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-0-85745-933-6.

- ^ de la Serna, Juan M. (1997). "Abolition, Latin America". In Rodriguez, Junius P. (ed.). The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery, Volume 1; Volume 7. ABC-CLIO. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0874368855. OCLC 185546935. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Aponte, Sarah; Acevedo, Anthony Steven (2016). "A century between resistance and adaptation: commentary on source 021". New York: CUNY Dominican Studies Institute.

This constitutes the first documented mention that we know of, in a primary source of that time, of acts of resistance by enslaved Black people in La Española after the uprising of December 1521 across the south-central coastal plains of the colony, an event first reflected in the ordinances on Black people of January, 1522, and much later in the well-known chronicle by Fernández de Oviedo.

- ^ Tierney, Brian (1997). The Idea of Natural Rights: Studies on Natural Rights, Natural Law, and Church Law, 1150-1625. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 270–272. ISBN 0802848540.

- ^ Aspinall, Dana E.; Lorenz, Edward C.; Raley, J. Michael (2015). Montesinos' Legacy: Defining and Defending Human Rights for Five Hundred Years. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1498504140.

- ^ Clayton, Lawrence A. (2010). Bartolome de las Casas and the Conquest of the Americas. John Wiley & Sons. p. 175. ISBN 978-1444392739.

- ^ Castro, Daniel (2007). Another Face of Empire: Bartolomé de Las Casas, Indigenous Rights, and Ecclesiastical Imperialism. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822389590.

- ^ Elliott, John Huxtable (2014). Spain, Europe & the Wider World, 1500-1800. Yale University Press. pp. 112–121, 198–217. ISBN 978-0300160017.

- ^ Phillips, William D. The Middle Ages Series : Slavery in Medieval and Early Modern Iberia. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 14.

- ^ Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery, pp.34-44.

- ^ Phillips, William D. The Middle Ages Series : Slavery in Medieval and Early Modern Iberia. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- ^ Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery, pp. 50-51.

- ^ quoted in Blackburn,The Making of New World Slavery, p. 51.

- ^ Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery, pp. 62-63, 81-82.

- ^ Lockhart and Schwartz, Early Latin America, pp. 21-22.

- ^ Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery, pp. 62-63, 81-82.

- ^ Lockhart and Schwartz, Early Latin America, pp. 21-22.

- ^ Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery, pp. 62-63, 81-82.

- ^ Van Dantzig, Albert (1975). "Effects of the Atlantic Slave Trade on Some West African Societies". Outre-Mers. Revue d'histoire. 62 (226): 252–269. doi:10.3406/outre.1975.1831.

- ^ Lockhart and Schwartz, Early Latin America, pp. 26-28.

- ^ Lockhart and Schwartz, Early Latin America, pp. 21-22.

- ^ "Bartoleme de las Casas". Oregonstate.edu. Archived from the original on December 26, 2002. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- ^ Guitar, Lynne, No More Negotiation: Slavery and the Destabilization of Colonial Hispaniola's Encomienda System, by Lynne Guitar, retrieved 2019-12-06

- ^ Indian Slavery in the Americas- AP US History Study Guide from The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, 2012-03-22, archived from the original on 2021-03-08, retrieved 2019-12-06

- ^ Robert Himmerich y Valencia, The Encomenderos of New Spain, 1521–1555, Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991 p. 178

- ^ "La encomienda en hispanoamérica colonial". Revista de historia (in Spanish). 2020-08-26. Retrieved 2021-01-06.

- ^ Gunst, Laurie. "Bartolomé de las Casas and the Question of Negro Slavery in the Early Spanish Indies." PhD dissertation, Harvard University 1982.

- ^ Juan Friede and Benjamin Keen, Bartolome de las Casas in History. Toward an Understanding of the Man and His Work Northern Illinois University Slavery Press, 1971. ISBN 0-87580-025-4

- ^ a b Herzog, Tamar (2018). "Indigenous Reducciones and Spanish Resettlement: Placing Colonial and European History in Dialogue". Ler História. 72 (72): 9–30. doi:10.4000/lerhistoria.3146. S2CID 166023363.

- ^ Acemoglu, Daron; Robinson, James A. (2012). Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity, and poverty (1. ed.). New York, NY: Crown Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-0307719218. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ a b c Scarano, Francisco A. (2012). "Spanish Hispaniola and Puerto Rico". In Smith, Mark M; Paquette, Robert L (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199227990.013.0002. ISBN 978-0-19-922799-0.

- ^ Paquette, Robert L. & Mark M. Smith. "Slavery in the Americas". www.academia.edu. Archived from the original on 2020-04-14. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- ^ Rupert, Linda M. (September 2009). "Marronage, Manumission and Maritime Trade in the Early Modern Caribbean". Slavery & Abolition. 30 (3): 361–382. doi:10.1080/01440390903098003. S2CID 143505929.

- ^ a b Urbina, Rodolfo (1990). "La rebelión indígena de 1712: los tributarios de Chiloé contra la encomienda" [The Indigenous Rebellion of 1712: The Tributaries of Chiloé Against the Encomienda] (PDF). Tiempo y espacio [Time and Space] (in Spanish) (1). Chillán: El Departamento: 73–86.

- ^ "La rebelión huilliche de 1712". El Llanquihue (in Spanish). 29 July 2007. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- ^ "La encomienda". Memoria chilena (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de Chile [National Library of Chile]. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ Villalobos, Sergio; Silva, Osvaldo; Silva, Fernando; Estelle, Patricio (1974). Historia De Chile. Editorial Universitaria. p. 237. ISBN 978-9561111639.

- ^ a b "Laws of the Indies". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ a b "Encomienda". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 26 September 2008. Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Bakewell, Peter (1984). "Mining in colonial Spanish America". The Cambridge History of Latin America. Vol. 2, Colonial Latin America. 2: 127. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521245166.005. ISBN 9781139055178.

- ^ Spodek, Howard (February 2005). The World's History, Third Edition: Combined Volume (pages 457-458). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-177318-9.

- ^ Burkholder, Mark; Johnson, Lyman (2012). Colonial Latin America (8th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Tutino, John (2018). The Mexican Heartland: How Communities Shaped Capitalism, a Nation, and World History, 1500-2000. Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvc774tz.5. ISBN 978-0-691-17436-5. JSTOR j.ctvc774tz.

- ^ Tutino, John (2018). "Silver Capitalism and Indigenous Republics". Silver Capitalism and Indigenous Republics: Rebuilding Communities, 1500–1700. Princeton University Press. p. 71. doi:10.2307/j.ctvc774tz.5. ISBN 9780691174365. JSTOR j.ctvc774tz.5.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Blackburn, Robin (1998). The Making of New World Slavery: From the Baroque to the Modern, 1492-1800. Verso. p. 134. ISBN 1859841953.

- ^ Simpson, Lesley Byrd (1929). The Encomienda in New Spain. University of California Press.

- ^ Guzmán, Carmen Luz (2013). "Las cautivas de las Siete Ciudades: El cautiverio de mujeres hispanocriollas durante la Guerra de Arauco, en la perspectiva de cuatro cronistas (s. XVII)" [The captives of the Seven Cities: The captivity of hispanic-creole women during the Arauco's War, from the insight of four chroniclers (17th century)]. Intus-Legere Historia (in Spanish). 7 (1): 77–97. doi:10.15691/07176864.2014.0.94 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "Philip III, had taken the drastic step of stripping indigenous "rebels" of the customary royal protection against enslavement in 1608, thus making Chile one of the few parts of the empire where slave taking was entirely legal." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 127-128). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ a b Valenzuela Márquez, Jaime (2009). "Esclavos mapuches. Para una historia del secuestro y deportación de indígenas en la colonia". In Gaune, Rafael; Lara, Martín (eds.). Historias de racismo y discriminación en Chile (in Spanish). pp. 231–236.

- ^ Urbina Burgos, Rodolfo (2007). "El pueblo chono: de vagabundo y pagano a cristiano y sedentario mestizado". Orbis incognitvs: avisos y legados del Nuevo Mundo (PDF) (in Spanish). Huelva: Universidad de Huelva. pp. 325–346. ISBN 9788496826243.

- ^ Barros Arana, Diego (2000) [1884]. Historia General de Chile (in Spanish). Vol. IV (2 ed.). Santiago, Chile: Editorial Universitaria. p. 341. ISBN 956-11-1535-2.

- ^ "Why were Africans enslaved?". International Slavery Museum. Retrieved 2018-10-05.

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (2001). "The Ideology of Racial Hierarchy and the Construction of the European Slave Trade". Black Renaissance. 3 (3): 133–146. ProQuest 215522164.

- ^ Martínez, María Elena (1 July 2004). "The Black Blood of New Spain: Limpieza de Sangre, Racial Violence, and Gendered Power in Early Colonial Mexico". William and Mary Quarterly. 61 (3): 479–520. doi:10.2307/3491806. JSTOR 3491806.

- ^ Gift, Sandra Ingrid (2008). Maroon Teachers: Teaching the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Africans. Kingston, Jamaica: Ian Randle Publishers. ISBN 9789766373405.

- ^ Parker, Susan (2019-08-24). "'1619 Project' ignores fact that slaves were present in Florida decades before". St. Augustine Record. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ a b Francis, J. Michael; Mormino, Gary; Sanderson, Rachel (2019-08-29). "Slavery took hold in Florida under the Spanish in the 'forgotten century' of 1492-1619". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ a b Torres-Spelliscy, Ciara (2019-08-23). "Perspective - Everyone is talking about 1619. But that's not actually when slavery in America started". Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ Codex Telleriano-Remensis, translated and edited by Eloise Quiñones Keber. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992:275.

- ^ a b Hankerson, Derek (2008-01-02). "The journey of Africans to St. Augustine, Florida and the establishment of the underground railway". Patriotic Vanguard. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ Gardner, Sheldon (2019-05-20). "St. Augustine's Fort Mose added to Slave Route Project". St. Augustine record. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ a b c Baralt, Guillermo A. (2007). Slave Revolts in Puerto Rico: Conspiracies and Uprisings, 1795-1873. Markus Wiener Publishers.

- ^ Rogozinsky, Jan. A Brief History of the Caribbean. Plume. 1999.

- ^ Kitchin, Thomas (1778). The Present State of the West-Indies: Containing an Accurate Description of What Parts Are Possessed by the Several Powers in Europe. London: R. Baldwin. p. 12.

- ^ a b "Teoría, Crítica e Historia: La abolición de la esclavitud y el mundo hispano" (in Spanish). Ensayistas.org. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- ^ a b "El 'Bando Negro' o "Código Negro"" [The "Black Edict" or "Black Code"]. Government Gazette of Puerto Rico (in Spanish). fortunecity.com. May 31, 1848. Archived from the original on June 6, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Martinez, Robert A. "African Aspects of the Puerto Rican Personality". ipoaa.com. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ Montejo 2016, p. 40

- ^ a b Montejo 2016, pp. 39–40

- ^ "Transatlantic Slave Trade | Slavery and Remembrance". slaveryandremembrance.org. Retrieved 2025-02-05.

- ^ a b c Childs, Matt D. (2006). 1812 Aponte Rebellion in Cuba and the Struggle against Atlantic Slavery. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5772-4.

- ^ "Slavery in the Americas | Slavery and Remembrance". slaveryandremembrance.org. Retrieved 2025-02-05.

- ^ Montejo 2016, pp. 80–82

- ^ Knight pp. 144–145

- ^ a b Montejo 2016, p. 39

- ^ a b Brunson, Takkara (2024-04-12). "Race and Reproduction in Cuba, by Bonnie A. Lucero". New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids. 98 (1–2): 159–160. doi:10.1163/22134360-09801014. ISSN 2213-4360.

- ^ Borrego, Pedro Damián Cano (2019). "La libertad de los esclavos fugitivos y la milicia negra en la Florida española en el siglo XVIII". Revista de la Inquisición: ( intolerancia y derechos humanos ) (23): 223–234. ISSN 1131-5571 – via dialnet.unirioja.es.

- ^ Patrick Riordan (Summer 1996). "Finding Freedom in Florida: Native Peoples, African Americans, and Colonists, 1670-1816". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 75 (1). Florida Historical Society: 25–31.

- ^ Sylvester A. Johnson (6 August 2015). African American Religions, 1500–2000: Colonialism, Democracy, and Freedom. Cambridge University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-316-36814-5.

- ^ a b Miller, E: "St. Augustine's British Years," The Journal of the St. Augustine Historical Society, 2001, p. 38. .

- ^ Alexander Deconde, A History of American Foreign Policy (1963) p. 127

- ^ Weeks (2002)[full citation needed]

- ^ Bas García, José R. (March 23, 2009). "La abolición de la esclavitud de 1873 en Puerto Rico" [The abolition of slavery in 1873 in Puerto Rico]. Center for Advanced Studies of Puerto Rico and the Caribbean (in Spanish). independencia.net. Archived from the original on March 19, 2011.

- ^ Rodriguez 2007a, p. 398.

- ^ "Esclavitud Puerto Rico". Proyectosalonhogar.com. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Stone, Erin Woodruff (2021). Captives of Conquest: Slavery in the Early Modern Spanish Caribbean. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-9958-8.